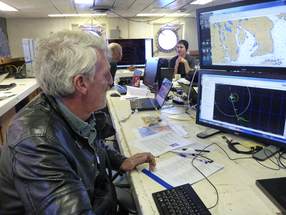

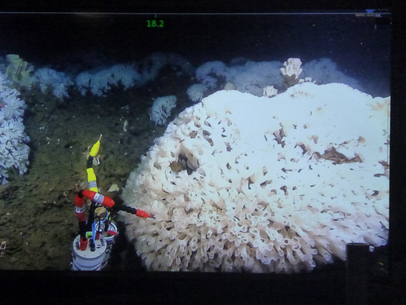

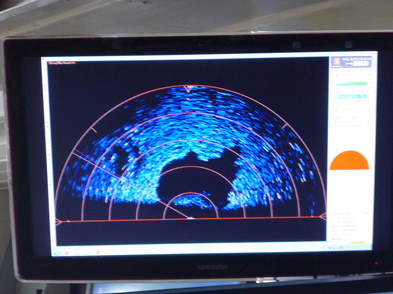

PART I Sept 28 – Fly to Terrace – Amanda and I meet at the Edmonton Airport with the Aquadopp borrowed from Len Zedel Memorial (last minute to replace one we were kindly offered from Verena, which was not after all a profiler) and a bin of last minute gear. Transit via Calgary (hope AC doesn’t misplace the bags) to Terrace, with an amazing flight up the Rockies to a part of BC few people seem to go to (the plane was quite empty but we had to sit in the back half to ‘balance’ it according to the steward).  Met at the Airport by Verena’s crew and Raymond from Norway – jetlagged but not showing it! Terrace is a one baggage carousel airport (if that), but Hertz was ready and we had two vehicles so we headed off for lunch in town (guided by Raymond who’d been there one night…shows the size of the town) and then to Kitimat, a 30 min drive. We found the Kitimat Hotel to confirm water taxi transfers (more for our own peace of mind than for theirs, because Tracy John Hittel was the model of efficiency). We touch bases with the CG JPTully by email and confirm we can transfer at 6pm rather than 7, allowing us another hour to get to Verena’s first site. The MK marina is about 15 min down the east side of the fjord, and right on time we find the Tully there putting the small boat (hurricane inflatable) in the water to transfer Kim Conway’s group ashore. It is a car handoff, and a quick hello/goodbye and we are off to the Tully which is standing by. How to get onto a 70m ship from an inflatable? We climb the ladder (yes!..all eyes watching in case we’d had one too many ashore…had not!) On board, as the ship moves to the first dive site as Chief Officer Rhona runs through our safety and ship introductions; we then settle in to cabins and the lab. Sept 29 – On the CCGS JP Tully Breakfast at 6 – lots; lunch at 11.30 mmm; supper at 5 – better have left room. Dafne, Raymond, Amanda and I unpacked and begin to assemble the instruments, staying clear of Verena’s team who are diving the fjord walls. Amanda starts shifting herself to night shift, and helps out on late night fjord dives, while the three of us have equipment yoga on the floor. These instruments require assembly (IKEA type) not only into their housings (programmed, checked and ‘running’ or ‘ready to run’) but need to be bolted using hose clamps onto spikes that we hold with the robotic arm by a ‘hockey puck handle’ and skewer into the dead reef beside sponges. This requires power drills as well as some athletics. But they work! Like a charm :)  Ray finding us a gunkhole...Fish Bay! Ray finding us a gunkhole...Fish Bay! Oct 1st – Hartley Bay, Douglas Channel Verena’s overnight dive ends at 7am – as requested by the captain (7-7 if possible), the former is easy, but the latter is difficult given the need for 2-3hour turnarounds of the ROV and transits between sites. Verena has accommodated by having some transits ‘in the water’ at 1knot the speed the ROV can do…but once this caught us in some mid-water derelict fishing gear which ROPOS had to cut itself out of (lost one knife in a nailbiting moment…but the other worked!)…so it’s not clear it is a good solution. The captain thinks the weather might last until tomorrow (winds are currently calm-ish offshore but are forecast to rise) and suggests Verena forego her morning dive to allow us (the next group) to head out to the reefs. She nicely agrees and her party leave in the small boat to meet Tracy with the new group from Kitimat. These board the ship with vigor – Evgeni, Lauren, Clark, Tristan and Jason – and are given their ‘tour’ by one of the ship’s mates, and then settle in as we head 8 hours out to the working site. By the time we get there the winds are up to 27 knots and rising. It’s not possible to put ROPOS in let alone be sure to recover - all bets are off and we head back (another 8 hours) with me pouring over the charts with Ray to find a gunkhole for the Tully and ROPOS, that is a place to dive in which the ship can hide from the winds so it can position well, but also with some soft ground that I can plant my instruments in to calibrate, and with the hope of some nice sponges to start basic measurements on.  Oct 2 – Fish Bay – Squally Reach. My objective here is to save time when at the reefs by calibrating the thermistor flow meters in situ. These are ‘old-fashioned’ instruments that I have built from bits and pieces – boards engineered by retired electronics tech Pat Kerfoot, probes built 3 times by Jeremy in Oregon, housings from Oregon, and the composite and temperature compensations by me and in former years by Dafne. They are awkward but work, like no other flow meter works for a sponge as that we are to deal with. We need a probe that can enter a hole no larger than 2-3 cm in diameter and robustly record the flow. They have their issues… I can and probably will write a small book on it, but for now my goal is to put them down in the same water temperature the reef sees, more-or-less, together with an off-the-shelf instrument I bought two years ago, the Vector (usually this name conjures up many memories for those of us who have dived with the Vector for the last 2 years!). We use the Vector to calibrate the thermistor probes. By leaving them with the Vector, positioned so that both thermistors are at the same height as the Vector we get a data record of voltages from the thermistors that corresponds to a data record of water velocities from the Vector. You have to understand that water flow is not laminar at these sites…nor at the reef, and so each instrument sees such a range of flows and directions that it would not make any sense unless you had several hours of such flows to determine what the best correlations were and from those make the calibrations. Often an overnight deployment is best. This depends on where we intend to be the next day!  Oct 3rd – Fish Bay perhaps the weather is improving – at least the captain thinks it might (my Windalert.com does not think so) but on the hope that it will we head off in the morning to the reef site, another 8hr venture. We get there to find 30knot winds and now seas are 3 meters and rising so we veer off to the west side of Banks Island with the thought that ‘perhaps we can find a spot to work there, closer to the reefs’. The ship lolls, and sags, and a group meeting I call in good faith in the officers lounge sees me feeling a bit green and given the little enthusiasm I read in the responses from all, I call it off to get fresh air and worry about ‘where to go next’ (or where we are heading!). Our search for ‘working waters’ close to Banks takes us up to the north end of Banks Island where we end up desperately diving in a nothing (nothing against it per se) inlet called Beaver Pass. Amanda and her night crew bravely see out 9 hours (10pm to 7am) getting SIP water samples from the 3 Aphrocallistes cloud sponges they found. Beaver Pass is probably too exposed…or who knows why there are so few…but they like good water flow and not direct waves. But, she did a world of good that night because the ROPOS team are not only learning how to maneuver the SIP samplers and spot flow and oxygen meter on a ‘wand’ but they’re hungry for better sponges to test themselves in. Our water processing crew also leap to the challenge and whip through the first samples showing that their previous days practise (and many days practise on shore) has served well and that we have perfect results – more ammonia in the excurrent water than incurrent. This analysis takes all day (or all night) and is seen through by Tristan and Lauren, and with time by Anna and Kristen. We also learn how to ‘turn around’ the SIP samplers in better and better time…with Raymond, Clark, and Kristen and especially Evgeni the master, getting this to a fine tuned art.  October 4th – Anger Island – We transit down Principe Channel in search of potential Farrea to work on, but otherwise a decent Heterochone. We are looking for their filtration rates (spot flow) and metabolism (spot oxygen) as well as what they feed on (SIP water samples). It’s a beggars existence but we are rewarded for our efforts with solid numbers and with images of corals on the fjord walls, huge vase sponges, and the occasional octopus! (oh, and fishing gear…cannot get away from that and yet we trace it up the wall with ROPOS to be sure we are not, and will not get entangled in it.)  Raymond leaving by 'small boat' Raymond leaving by 'small boat' October 5th – Fish Bay, Squally Reach We can work on Heterochone here, and are ‘close’ to the reefs (a mere 8 hours). Do we move further up the fjord in search of Farrea or be ready for a weather window… I think this is the best move. Unfortunately both Jason and Raymond must leave today, mostly due to long-ago made plans that we all silently wish we could change since the winds are forecast to ease now for a 24hour window, switch direction and come as a full-blown gale from the south late on Oct 6th We make plans to drop the two off in the small boat (appropriately dressed) so that they can meet the water taxi from Kitimat. We head out to the reefs and intercept the small boat as it returns with the two new crew (Anna and Kristen) and continue to ‘Site 2’.  Site 2 – Hecate Strait sponge reefs – picked because we had been here in 2012 and of the 12 dives we did this was the one with the most sponges…the others having very little to none. We arrive at 1pm, probably using both engines to make it there so promptly, and ready to dive. The plan is no longer to ‘survey the reef and see where we’ll work’, instead, given the impending storm, I plan to put down all instruments (two Aquadopps, the Vector, and two double can thermistor oxygen sensors) over two sponges and then continue with the mapping for the whole night. The water is almost calm! And we descend fully prepared into the calm… and it is as doing a night dive on a tropical reef. The water is clear – so clear – unlike my experience of reefs in the Strait of Georgia. And the sponges are white, so white. I’ve seen these before in 2012, but it didn’t ring home then. Compared to the SoG reefs these are so white. They’re also Farrea the dome of white lacy frills, everywhere…and Heterochone plunging up out of the domes. White..but what a lot of fish, red and yellow everywhere. Crabs and seastars, crinoids, and huge halibut, life abounds. We position the instruments focusing on precision, and then leave them – knowing full well that with the GAPS and LOKI positioning system we can find these in a snowstorm at 170 meters in the middle of Hecate Strait (niceJ). Our survey starts, Lauren aiming to establish the percentage of coverage of live sponge and compare that to what Kim suggests is reef from side scan sonar.  Quickly we figure out that sponge reef looks totally black on the sonar – unlike regular sand/mud bottom – so we can soon see when we’re about to head into a dense reef patch and come out of it. Cool. I leave the night shift to the joy of watching reef – and so a pattern emerges in which the night shift flies around beautiful sponges all night while we of the day do fiddly work with plastic and instruments or mud or such (we are each jealous of each other, wishing to stay awake to see both parts!). October 6 – Hecate reefs Still calm, as predicted! So we head down to the closest ‘different’ site, Stn3 Peleponesus, which should be an abundance of sponge according to Kim’s side scan sonar. Mapping begins, and without leaving the bottom, but imaging every 25m we soon find that there’s more mud than sponge. Sponges exist, but it’s not at all even like Stn2 where we started. We carry out 50 of the 25m points before we must sample a couple of SIPs and surface to return to recover the instruments…the storm is on its way. THE RECOVERY....  Pancaked instruments - we got them all back in one go! and with care... Pancaked instruments - we got them all back in one go! and with care... Oct 6th – evening. A calm discussion – there’s concern – the weather… the storm. Two dives might not be possible, let’s haul in one. How? We deployed it all in two. The pilots merge, disperse and work with ROPOS, and it’s now configured with enough straps to get all in one go. We descend and the reef is as we left it. Serene, fish eying us but not moving, halibut swooping by, seastars munching. Instruments sampling. We begin what I call pancaking them on to the platform, one by one; and within an hour and a half we have all of them mounted and read to haul. Remarkably – all instruments recorded data! What I haven’t mentioned yet is that 2 of the 3 oxygen sensors leaked water into the housings on their fjord deployments. 2 inches of water poured out of one can, but the instrument still worked. I decided to risk a second deployment at the reefs. What else was I here for anyway? We unloaded the pancake stack, rinsed everything and began opening housings. Water in the oxygen sensors, and one had stopped working – but only on recovery! So I had all 24hours recording. The other continued to work – though I can’t talk to it through its software (something is corroded there) so we wrap it in plastic and deploy it as an ‘on the wand’ instrument together with a flowmeter for ‘spot flow/oxygen’. The weather is holding – a curious nervous-ness is felt, and yet Keith says we dive again, but ‘free’, except for a box to put samples in, so we can haul at any time. We continue our map and collect precious tissues for fixation – samples to confirm our physiology. The mapping, water sampling and image capture continue through the night. I wake at 2 after going to bed at midnight – was there something different in the wind? – downstairs in the lab all is normal…so back to sleep at 3. Up at 5 – wind must be up. Jon and I agree swells are larger in the dark. Keith awakes, and the crew shift to haul ROPOS at 6 before breakfast. On deck with precious tissue samples to process we charge off to the north, with the waves, once again circumnavigating Banks Island to avoid the growing seas behind us. Tissues are fixed in ethanol, aldehydes and for electron microscopy …dataloggers downloaded…. Images filed. People go to sleep, a long transit begins (where to go?) – I have emailed with Kim Conway and decided on one of his options – not north to Alaska sadly where there’s a reef at Portland Canal – but south to Malcolm Island, where there might be enough lee to allow a dive at ‘the fastest growing reef known”….that is half way back to home port anyway! And I aim to show Lauren and Tristan Fraser Ridge and do some sediment experiments there…

0 Comments

Getting to Hecate Strait might appear fairly simple for people boarding at a harbor. You just walk onto the boat and steam over to your destination. However, none of our scientists or ROPOS crew members left Patricia Bay (Victoria, BC) aboard the J.P. Tully, since the Tully had another operation before our cruise. This meant that everyone had to work their way up north, to Kitimat, BC. The first crew was able to board at Kitimat harbor, so their travel plans consisted only of flying to Terrace (via Vancouver), and driving 45 minutes to Kitimat where they boarded the Tully.

|